This is just a service announcement to inform that I am on vacation and will not be blogging this week. Friday two weeks from now all will be back to normal.

Happy New Year!

Friday 28 December 2018

Friday 14 December 2018

Bullitt (1968)

After a screening of Bullitt (Peter Yates 1968) my students spent some time discussing who exactly Chalmers was (the character played by Robert Vaughn) and what exactly had happened. Who was killed in the hotel room and who was shot at the airport? I find it exhilarating that the film is so oblique. Those who made it were not deliberately trying to be confusing but there is hardly any exposition. Since everybody in the film know each other and are on the same page they do not spend time telling each other things they already know but that might be beneficial for us. The film is patient, meticulous and meandering, so it is not impossible to follow what is happening, but in order to grasp the significance of what is happening and where the police investigation of that first murder takes us, you need to pay attention. The film is not giving anything away for free and does not provide summaries or explanations. I think the approach of Yates and scriptwriters Alan R. Trustman and Harry Kleiner shows a level of trust in the audience, a belief in our attention span and cognitive abilities. Such respect is frequently lacking among filmmakers of mainstream hits today, where characters often provide a running commentary on all that is happening, has happened and will happen.

Bullitt, which I have seen many times, has more good things to offer besides this trust. It is for example one of the great films of San Francisco and uses the locations to utmost effect, not only in the celebrated car chase. The cinematography by William A. Fraker is overall very good and the film combines stylish, moody shots with raw, naturalistic shots, all helping to create the mood and style of a film both artful and real. That most of the film is without a score adds to this feeling. It is only in a few instances that Lalo Schifrin's jazzy score appears, and then quickly disappears again.

Clearly I am very fond of Bullitt, including the nice scene where Bullitt/McQueen goes shopping for groceries in a small corner shop, but I am also interested by the history behind the production of it, and its transitional place in Hollywood cinema. It was made just as what is frequently, and often confusingly, labelled "New Hollywood" is said to have begun, although Bullitt is rarely spoken off in relation to films such as Bonnie and Clyde (Arthur Penn 1967) or The Graduate (Mike Nichols 1967). But it is as interesting (and as a film better) as those two, and several others. It was also made the same year as Madigan (Don Siegel 1968), with which it has some similarities but also important differences.

Steve McQueen had just started his own production company, Solar Productions, with Robert E. Relyea, and, with Solar having cut a deal with Warner Bros.-Seven Arts, McQueen had almost full control over the making of Bullitt. Its producer was Philip D'Antoni, whose focus was also on gritty naturalism, but McQueen had the script, hired the writers, oversaw the casting and hired the director, and made sure everything stayed true to how he envisioned the film. But he and the director, Yates, seem to have had the same idea, of making it as true to life as possible. McQueen wanted Yates after having seen his film from 1967, Robbery, and Bullitt would be Yates's first American film. The films are not particularly similar except for the emphasis on real locations and as little exposition as possible. But what seems to primarily have caught McQueen's interest was the car chase that opens Robbery, through the streets of London. A car chase is also what Bullitt is most famous for, here on the streets of San Francisco. The emphasis is again on naturalism, with McQueen partly driving himself and instead of music there is only the sounds of engines and tyres. It is a powerful effect, and it gives the chase a peculiar feeling. The shooting of it keeps the cars in their context, so you are very aware of where they are in relation to each other, to other cars, other buildings and in San Francisco. It is the opposite of car chases in for example The Bourne Supremacy (Paul Greengrass 2004) in which everything is fragmented and dislocational.

But already three years after Bullitt, William Friedkin staged the car chase in French Connection (1971, also produced by D'Antoni) in a distinctly more chaotic way than Bullitt and with more emphasis on cutting than long takes. A development which could be seen as an example of what David Bordwell refers to as "intensified continuity". The look of French Connection overall is also rougher than Bullitt, which feels smoother or warmer (I am not sure which words are most helpful). Another way of putting it is that cinematographer Owen Roizman's style of shooting and lighting French Connection is not the same as Fraker's on Bullitt, and the style of shooting and lighting in the 1960s differs, on average, from the 1970s. A combination of different artistic choices and larger historical trends.

After French Connection, Philip D'Antoni made The Seven-Ups (1973) as an unacknowledged sequel, this time as director as well as producer. It too has an elaborate car chase but for each film they seem to lose something. Yates is a better director than both Friedkin and D'Antoni. Another person who needs to be mentioned is the stunt driver Bill Hickman, who played a part in designing the chase of Bullitt. He also plays the hitman who drives the car McQueen is pursuing, and he also drove the car in the chase in French Connection as well as a car in The Seven-Ups.

Siegel's Madigan, mentioned above, is similar in structure to Bullitt (a few days during which two weary cops look for a killer) and while Siegel also aimed for realism and verisimilitude, he was unable to convince the producers to shoot it all in actual locations and it shows. It does diminish the film, however good Richard Widmark is in the title role, and however excellent the staging of individual scenes is. It is also a plot-heavy film, with several parallel stories unfolding, which is an important difference from Bullitt too. A similarity though is the unpredictability of them. It is part of the appeal of these police thrillers from this time that you do not know whether the main character will get killed or not in the end. Sometimes they die, sometimes they live. Even when re-watching one of them I sometimes catch myself wondering how it will end this time.

Another point of comparison is with Siegel's earlier thriller The Lineup (1958). It has a very different plot (two contract killers clearing up after a failed drug delivery) but it is shot on location in San Francisco and it has a good car chase. It is one of Siegel's very best films, and while it cannot be said to be an inspiration for Bullitt, it is a reminder that the latter was not the first car chase through San Francisco. But the sequence in Bullitt is significantly longer, more complex and advanced. It is something new.

Bullitt was a key film in McQueen's career, and one of his biggest successes at the box office. It is also a key film in Yates's career. Yates made three great police thrillers, Robbery, Bullitt and The Friends of Eddie Coyle (1973) but despite his obvious skills it is probably right to say that on Bullitt it was McQueen who was the most influential person on set.

McQueen and Vaughn

Bullitt, which I have seen many times, has more good things to offer besides this trust. It is for example one of the great films of San Francisco and uses the locations to utmost effect, not only in the celebrated car chase. The cinematography by William A. Fraker is overall very good and the film combines stylish, moody shots with raw, naturalistic shots, all helping to create the mood and style of a film both artful and real. That most of the film is without a score adds to this feeling. It is only in a few instances that Lalo Schifrin's jazzy score appears, and then quickly disappears again.

Clearly I am very fond of Bullitt, including the nice scene where Bullitt/McQueen goes shopping for groceries in a small corner shop, but I am also interested by the history behind the production of it, and its transitional place in Hollywood cinema. It was made just as what is frequently, and often confusingly, labelled "New Hollywood" is said to have begun, although Bullitt is rarely spoken off in relation to films such as Bonnie and Clyde (Arthur Penn 1967) or The Graduate (Mike Nichols 1967). But it is as interesting (and as a film better) as those two, and several others. It was also made the same year as Madigan (Don Siegel 1968), with which it has some similarities but also important differences.

Jacqueline Bisset with McQueen

Steve McQueen had just started his own production company, Solar Productions, with Robert E. Relyea, and, with Solar having cut a deal with Warner Bros.-Seven Arts, McQueen had almost full control over the making of Bullitt. Its producer was Philip D'Antoni, whose focus was also on gritty naturalism, but McQueen had the script, hired the writers, oversaw the casting and hired the director, and made sure everything stayed true to how he envisioned the film. But he and the director, Yates, seem to have had the same idea, of making it as true to life as possible. McQueen wanted Yates after having seen his film from 1967, Robbery, and Bullitt would be Yates's first American film. The films are not particularly similar except for the emphasis on real locations and as little exposition as possible. But what seems to primarily have caught McQueen's interest was the car chase that opens Robbery, through the streets of London. A car chase is also what Bullitt is most famous for, here on the streets of San Francisco. The emphasis is again on naturalism, with McQueen partly driving himself and instead of music there is only the sounds of engines and tyres. It is a powerful effect, and it gives the chase a peculiar feeling. The shooting of it keeps the cars in their context, so you are very aware of where they are in relation to each other, to other cars, other buildings and in San Francisco. It is the opposite of car chases in for example The Bourne Supremacy (Paul Greengrass 2004) in which everything is fragmented and dislocational.

But already three years after Bullitt, William Friedkin staged the car chase in French Connection (1971, also produced by D'Antoni) in a distinctly more chaotic way than Bullitt and with more emphasis on cutting than long takes. A development which could be seen as an example of what David Bordwell refers to as "intensified continuity". The look of French Connection overall is also rougher than Bullitt, which feels smoother or warmer (I am not sure which words are most helpful). Another way of putting it is that cinematographer Owen Roizman's style of shooting and lighting French Connection is not the same as Fraker's on Bullitt, and the style of shooting and lighting in the 1960s differs, on average, from the 1970s. A combination of different artistic choices and larger historical trends.

After French Connection, Philip D'Antoni made The Seven-Ups (1973) as an unacknowledged sequel, this time as director as well as producer. It too has an elaborate car chase but for each film they seem to lose something. Yates is a better director than both Friedkin and D'Antoni. Another person who needs to be mentioned is the stunt driver Bill Hickman, who played a part in designing the chase of Bullitt. He also plays the hitman who drives the car McQueen is pursuing, and he also drove the car in the chase in French Connection as well as a car in The Seven-Ups.

Hickman in Bullitt

Siegel's Madigan, mentioned above, is similar in structure to Bullitt (a few days during which two weary cops look for a killer) and while Siegel also aimed for realism and verisimilitude, he was unable to convince the producers to shoot it all in actual locations and it shows. It does diminish the film, however good Richard Widmark is in the title role, and however excellent the staging of individual scenes is. It is also a plot-heavy film, with several parallel stories unfolding, which is an important difference from Bullitt too. A similarity though is the unpredictability of them. It is part of the appeal of these police thrillers from this time that you do not know whether the main character will get killed or not in the end. Sometimes they die, sometimes they live. Even when re-watching one of them I sometimes catch myself wondering how it will end this time.

The Lineup

Bullitt was a key film in McQueen's career, and one of his biggest successes at the box office. It is also a key film in Yates's career. Yates made three great police thrillers, Robbery, Bullitt and The Friends of Eddie Coyle (1973) but despite his obvious skills it is probably right to say that on Bullitt it was McQueen who was the most influential person on set.

------------------

By Yates I can also recommend, for example, Murphy's War (1971), a British war film with Peter O'Toole; The Hot Rock (1972), scripted by William Goldman; and Breaking Away (1979), his first cooperation with writer Steve Tesich.

Having too much exposition and dialogue directed to the audience rather than to any character in the film is obviously not a new thing. A film like On the Waterfront (Elia Kazan 1954) is not exactly subtle or oblique, and it has all kinds of speeches for our benefit rather than for the benefits of the characters. This is common enough in films. But then it at least serves some narrative or thematic purpose. Today it often feels like there is exposition for the sake of exposition. Maybe there is a fear of people being distracted by their mobile phones and therefore losing track of the story, or maybe a fear of being accused of plot holes. As a general rule, people who complain about plot holes have just not been paying enough attention. They would not like Yates's films.

Etiketter:

Don Siegel,

film history,

Peter Yates,

Steve McQueen

Friday 30 November 2018

Talking about neorealism

At a podcast from earlier this year about Ingmar Bergman's early films the participants excitedly said that his first film Crisis (1946) clearly showed how he was influenced by neorealism. This is impossible. Crisis was filmed in early 1945, long before any neorealist films had been shown in Sweden, and before Rome - Open City (Roberto Rossellini 1945) opened in Italy. Consequently, neorealism did not even properly exist in Italy when Bergman made his film. Besides, there is nothing in Crisis that particularly suggests neorealism, not style, subject matter or tone. As I wrote earlier this year it is rather reminiscent of a certain kind of American melodrama, like something by Douglas Sirk before Sirk had mastered his craft.

Another instant of neorealism confusion: Roberto Rossellini's films with Ingrid Bergman have all, with the exception of Joan of Arc at the Stake (1954), been called neorealist. But except Rossellini's first film with Bergman, Stromboli (1950), there is nothing particularly neorealist about them, whether Europe '51 (1952), Fear (1954) or Voyage to Italy (1954). The first is about a rich woman who decides to help society's downtrodden after the death of her son and the second is a thriller about a rich woman being blackmailed after having had an affair. The last, Voyage to Italy, is about a rich English couple on vacation in Italy as their marriage begins to fall apart. It is a beautiful film, one of the best ever made, but there is not much gained by calling it neorealist. (Even though André Bazin did call it that.)

Admittedly the neorealist films are different from one another. Open City and La terra trema (Luchino Visconti 1948) do not have that much in common. Bazin wrote in 1954 that "Rossellini's neorealism" could be seen as "very different from, if not the opposite of, De Sica's." We might not even talk of these films as being part of a group or cycle or movement if Cesare Zavattini and some others had not explicitly promoted their cause at the time, often in hyperbolic terms. They were often, not least Zavattini, claiming that their films were the opposite of Hollywood cinema. "In fact, the American position is the antithesis of our own" Zavattini said in 1952, in particular the neorealists' "hunger for reality", their "homage /.../ to other people." But there is no "American position." During the years of neorealism, that desire to capture reality and truths about people was not more common in Italy than in Hollywood. Clearly Gone with the Wind (1939) is very different from the neorealist films, but it is also very different from The Best Years of Our Lives (William Wyler 1946), which aims to do exactly what Zavattini says his films uniquely do. Shoeshine (Vittorio De Sica 1946), scripted by Zavattini, is rather close in tone and style to Warner Bros. films of the 1930s, to the extent that it might be seen as an homage to it. When thinking about Open City, it is of course very different from Anna and the King of Siam (John Cromwell 1946) but compare it instead to, say, The Story of G.I. Joe (William Wellman 1945). The neorealist films are not the opposite of such a film, and many of them are more conventional and more melodramatic than Wellman's film.

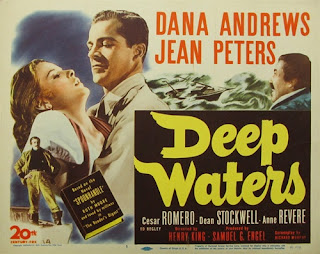

A very small percentage of Italian films from 1945 and to the early 1950s can in a meaningful way be called neorealist, on average maybe six or seven per year, among the close to 900 films that were made in Italy during those years. There are many ways of "capturing the truth" without the films being depictions of ordinary people in their daily environments but even if we, as I do here, restrict ourselves to such films, that still means that there were fewer neorealist films, like Bitter Rice (Giuseppe De Santis 1949), any given year than comparable films, like Deep Waters (Henry King 1948), from Hollywood.

Another way of defining neorealism is like this, from the website of BFI:

It is probably the case that a lot of the contemporary Italians' arguments about the break that neorealism allegedly constituted had to do with a wish to wash their hands of the Fascist years, even trying to hide their own part of it. Several of them had earlier made the kind of films they were now claiming to be revolting against, including Zavattini. Some, like Rossellini, had made films that were part of the comparatively few films that were Fascist propaganda. The neorealist approach is not in itself left-wing or right-wing, communist, fascist or conservative. Many causes can be served by trying to capture "the real Italy".

None of this diminishes the actual films that the neorealist cycle consists of; they are what they are, with their strengths and weaknesses, regardless of what we say about them. This brief article is only about the way they are talked about, and in particular the very word neorealism.

When Bergman's Crisis is referred to as neorealist it shows how the term has become detached from its specific meaning and instead refers to something considered realistic, diluting it of the meaning it might once have had. As soon as you use the term neorealist to talk about films not made in Italy just after the war, but about films made before and after and elsewhere in the world, the word loses its specific meaning and value. That seems unnecessary. Perhaps it is better to use the term to refer to that group of films as a whole, rather than to individual films; that the term's specific value comes from the combined force of the films and their unique context.

---------------

I said above that neorealism did not really exist in Italy before 1945 but I should add that the word "neorealist" was used by some Italian critics to describe Visconti's Ossessione when it came out in 1943.

The interview with Zavattini was re-printed in Sight and Sound 23:2 (October-December 1953), and that is from where my quote comes.

The Bazin quote about Rossellini and De Sica is from a chapter in the book Cinéma 53 à travers le monde (1954) and re-printed in André Bazin and Italian Neorealism (2011), p. 122.

In the same book, its editor Bert Cardullo celebrates De Sica's Umberto D. (1952) for its "strict avoidance of sentimentalism." (p. 28) Considering the relationship between the old man Umberto and his cute little dog, "strict avoidance" is not how I would define the film's relationship to sentimentalism...

I really like Deep Waters, a film about a small fishing community in Maine. The lobby card above has more drama in it than the actual film.

Another instant of neorealism confusion: Roberto Rossellini's films with Ingrid Bergman have all, with the exception of Joan of Arc at the Stake (1954), been called neorealist. But except Rossellini's first film with Bergman, Stromboli (1950), there is nothing particularly neorealist about them, whether Europe '51 (1952), Fear (1954) or Voyage to Italy (1954). The first is about a rich woman who decides to help society's downtrodden after the death of her son and the second is a thriller about a rich woman being blackmailed after having had an affair. The last, Voyage to Italy, is about a rich English couple on vacation in Italy as their marriage begins to fall apart. It is a beautiful film, one of the best ever made, but there is not much gained by calling it neorealist. (Even though André Bazin did call it that.)

Admittedly the neorealist films are different from one another. Open City and La terra trema (Luchino Visconti 1948) do not have that much in common. Bazin wrote in 1954 that "Rossellini's neorealism" could be seen as "very different from, if not the opposite of, De Sica's." We might not even talk of these films as being part of a group or cycle or movement if Cesare Zavattini and some others had not explicitly promoted their cause at the time, often in hyperbolic terms. They were often, not least Zavattini, claiming that their films were the opposite of Hollywood cinema. "In fact, the American position is the antithesis of our own" Zavattini said in 1952, in particular the neorealists' "hunger for reality", their "homage /.../ to other people." But there is no "American position." During the years of neorealism, that desire to capture reality and truths about people was not more common in Italy than in Hollywood. Clearly Gone with the Wind (1939) is very different from the neorealist films, but it is also very different from The Best Years of Our Lives (William Wyler 1946), which aims to do exactly what Zavattini says his films uniquely do. Shoeshine (Vittorio De Sica 1946), scripted by Zavattini, is rather close in tone and style to Warner Bros. films of the 1930s, to the extent that it might be seen as an homage to it. When thinking about Open City, it is of course very different from Anna and the King of Siam (John Cromwell 1946) but compare it instead to, say, The Story of G.I. Joe (William Wellman 1945). The neorealist films are not the opposite of such a film, and many of them are more conventional and more melodramatic than Wellman's film.

A very small percentage of Italian films from 1945 and to the early 1950s can in a meaningful way be called neorealist, on average maybe six or seven per year, among the close to 900 films that were made in Italy during those years. There are many ways of "capturing the truth" without the films being depictions of ordinary people in their daily environments but even if we, as I do here, restrict ourselves to such films, that still means that there were fewer neorealist films, like Bitter Rice (Giuseppe De Santis 1949), any given year than comparable films, like Deep Waters (Henry King 1948), from Hollywood.

There are different paths this article can take now. The argument could be that many are confused about what neorealism is, but that is not what interests me. The more interesting path to explore is how neorealism has never been defined in a way that is coherent and is therefore a very malleable term. The confusion is already in the word itself, "neorealism". There is nothing that is new with the films called neorealist. Films that try to capture the life of ordinary working-class people in a setting that aims to be as close to their natural environment as possible is almost as old as film history itself, as is the mixture of actors and amateurs that most neorealist films have. Some have claimed that what is new is the relation to time that the films express, but that is not necessarily related to realism and was not new either.

Therefore it is strange to call this film or that (such as People on Sunday (Robert Siodmak, Edgar G. Ulmer 1930), Our Daily Bread (King Vidor 1934) or Toni (Jean Renoir 1935)) precursors to neorealism because then it just becomes a synonym for realist films. The style and themes of neorealism are not unique enough for it to be relevant to say that earlier realist films were "pre-neorealist".

Yet neorealism does exist. I have here talked about them as a body of work, against which other films can be compared. Even if I say they are not new or different from all else I still clearly consider them as definable. And that comes from the particular time in which they appeared. They are the films made by a small group of filmmakers at a particular time in Italian history and which aimed, with various degrees of rigor, to depict the lives of ordinary Italians right after the end of the war, with Rossellini's Open City and Paisan (1946) being exceptions as they are set before the end of the war and about soldiers and underground fighters. The neorealist films were also about restoring the dignity of the Italian people. I assume however that it is now common knowledge that the neorealist films were to a large extent shot in studios and, when not using actual actors and stars, had amateurs that were type-casted and usually dubbed by others so that the face might be that of the amateur but the voice that of a professional. The films narrative structures are also frequently a lot more classical than was once assumed.Therefore it is strange to call this film or that (such as People on Sunday (Robert Siodmak, Edgar G. Ulmer 1930), Our Daily Bread (King Vidor 1934) or Toni (Jean Renoir 1935)) precursors to neorealism because then it just becomes a synonym for realist films. The style and themes of neorealism are not unique enough for it to be relevant to say that earlier realist films were "pre-neorealist".

Neorealism was above all a reaction to the studio-bound, Hollywood-influenced productions of the Fascist years (the so-called ‘White Telephone films’). Its proponents – Rossellini, Vittorio De Sica, Luchino Visconti, Giuseppe De Santis and Carlo Lizzani among others – were determined to take their cameras to the streets, to reflect the ‘real Italy’, which for years had been absent from Italian cinema screens.But this was not new for post-war Italian cinema. The critic Leo Longanesi wrote in 1933 that Italian filmmakers should move out on the streets and capture the lives of ordinary Italians and during the years of fascism such films were made, although I do not know an exact number. Neither do I know exactly how many "White Telephone films" that were made, but they do not make up all the many hundreds of films made in Italy during the years of Fascist rule. That was just one genre among many others.

It is probably the case that a lot of the contemporary Italians' arguments about the break that neorealism allegedly constituted had to do with a wish to wash their hands of the Fascist years, even trying to hide their own part of it. Several of them had earlier made the kind of films they were now claiming to be revolting against, including Zavattini. Some, like Rossellini, had made films that were part of the comparatively few films that were Fascist propaganda. The neorealist approach is not in itself left-wing or right-wing, communist, fascist or conservative. Many causes can be served by trying to capture "the real Italy".

None of this diminishes the actual films that the neorealist cycle consists of; they are what they are, with their strengths and weaknesses, regardless of what we say about them. This brief article is only about the way they are talked about, and in particular the very word neorealism.

When Bergman's Crisis is referred to as neorealist it shows how the term has become detached from its specific meaning and instead refers to something considered realistic, diluting it of the meaning it might once have had. As soon as you use the term neorealist to talk about films not made in Italy just after the war, but about films made before and after and elsewhere in the world, the word loses its specific meaning and value. That seems unnecessary. Perhaps it is better to use the term to refer to that group of films as a whole, rather than to individual films; that the term's specific value comes from the combined force of the films and their unique context.

---------------

I said above that neorealism did not really exist in Italy before 1945 but I should add that the word "neorealist" was used by some Italian critics to describe Visconti's Ossessione when it came out in 1943.

The interview with Zavattini was re-printed in Sight and Sound 23:2 (October-December 1953), and that is from where my quote comes.

The Bazin quote about Rossellini and De Sica is from a chapter in the book Cinéma 53 à travers le monde (1954) and re-printed in André Bazin and Italian Neorealism (2011), p. 122.

In the same book, its editor Bert Cardullo celebrates De Sica's Umberto D. (1952) for its "strict avoidance of sentimentalism." (p. 28) Considering the relationship between the old man Umberto and his cute little dog, "strict avoidance" is not how I would define the film's relationship to sentimentalism...

I really like Deep Waters, a film about a small fishing community in Maine. The lobby card above has more drama in it than the actual film.

Friday 16 November 2018

On films being dated

Last week there was a column in a Swedish newspaper about the year 1968, in particular its music. The writer compared some albums released that year with films and claimed that most films "feel hopelessly dated" and have "aged without any dignity" and mentioned as examples 2001, Where Eagles Dare, Planet of the Apes, Bergman's Hour of the Wolf and a Swedish farce, Åsa-Nisse och den stora kalabaliken, as opposed to the music which, he claimed, in general had aged well and was still very good.

My first reaction was, obviously, that the man was a fool and hey, there were many good films made in 1968 (Bullitt, Once Upon a Time in the West, Truffaut's Stolen Kisses, Bergman's Shame)! An angry tweet was forming. But on second thought it occurred to me that he had not said that all films were bad and that he might like those very films. By mentioning some good films from 1968 I would not disprove him and my tweet was discarded before posting. And he was right in the sense that most films from 1968 are probably not any good (imdb has 21,566 titles just from that year). But that is not something unique for films but true for works of art in general. We remember a few masterpieces and classics but the overwhelming majority of what has been created is not very good, and never was in the first place. The foolishness of him was for thinking that music was different from film. Sturgeon's law ("ninety per cent of everything is crap") probably applies there too. But such an observation is not particularly interesting.

You may think I am over-thinking that irrelevant column, written with no thought, but there is something interesting here, something this column was a good example of. The real flaw with the piece is very common, something I frequently criticise my students for, and which can even be seen as a common flaw in humans' conception of history. What does it actually mean to say that something is dated?

When that columnist said that most films have aged without dignity he made several assumptions from the fact that he did not like these films. If something has aged badly it must have been the case that it was once considered good but not so anymore. It would be weird to say that Ed Wood's films, like Plan 9 From Other Space (1959), have aged badly because they were never considered anything else than bad.

But I think we can assume that 2001, Åsa-Nisse and Where Eagles Dare are overall regarded much the same way now as in 1968. Hour of the Wolf is so strange and particular that it becomes meaningless to say it has aged in any direction. It was as weird in 1968 as it is now. You could argue instead that these films have not aged at all and the same kind of people who liked them then probably likes them now. I was a huge fan of Where Eagles Dare as a teenager, and I have it on blu-ray, but I find it a bit boring now. Not because the film has aged but because I have.

Planet of the Apes is somewhat different and it probably does not have the same kind of audience now as then. But what might conceivably be said to have aged are costumes and makeup, although I would not say they have aged without dignity. Quite the contrary.

And regardless of what one might think of those films they remain watched and liked and they continue to be a part of our culture. For that reason too it is also peculiar to argue that they have dated badly.

Some years ago a distinguished Swedish film critic said that after having re-watched The 400 Blows (François Truffaut 1959) he realised it was very dated. He did not like it as much as he once did. The presumption here is that during that time the film had changed, or aged, and he had not. I think you might more plausibly argue that it was the other way around.

The connection to my students is that they frequently say that a film is dated when they do not like it and say it was ahead of its time when they do like it. In view of the fact that they have not seen more than a small handful of older films they are not really in a position to argue whether something was ahead of its time or not. They have no frame of reference and only their prejudices to go on.

What is underlining all thinking about something being dated is an idea of progress. If an older film presents an idea of gender or sexual relations that someone today thinks is conservative or old-fashioned, she might say the film is dated; that when the film came out this was how everybody viewed gender and sexuality whereas now we have progressed and are more enlightened or some such.

But whatever view of gender or sexuality you might find in an older film can also be found in films today, and in society at large. If something is prominent today, and can be found in contemporary art, what does it mean to say it is dated? To what an extent must a view on for example social issues be less common today than it once was for that view to be considered dated? There are quite a few things in contemporary society I disapprove of but in many cases I am often in a very small minority when disapproving. It would not make any sense for me to say that a film from, say, 1952 is dated just because it is positive to one of those things I disapprove of if people today in general are just as positive about it as people were in 1952, whether I approve or not.

The beliefs that once a given film might have been considered a masterpiece but now we see that it is dated due to themes and subject matter; that something was of its time or ahead of its time; that nowadays we are wiser and more progressive and enlightened, are usually based on a smug ignorance, which can at times be quite intolerable.

It is a similar case with style. It is for example common to say that older films are slow, and that this makes them dated. As if His Girl Friday (Howard Hawks 1940) is slower than The Turin Horse (Bela Tarr 2011). Most of the current superhero films and Michael Bay's Transformers are pretty slow in the sense that they are very long, take their time, are to a large extent pointless exposition and in the end there are seemingly endless fight scenes of little value. Almost any given film from Fritz Lang' sound period, or from Darryl F. Zanuck or 1930s Warner Bros. or early Kurosawa or Bergman and so on is like a Lamborghini in comparison. Some would perhaps counter that I find The Avengers films slow because I find them uninteresting and yes, that is true. This is the point. Whether something is slow or not is a matter of personal preferences and somewhat irrelevant as a statement on cinema in general. Unless your argument is that today people find films interesting (and therefore not slow) whereas in them olden days people thought films were uninteresting and therefore slow.

There are also those who say that a film is dated because of what people wear or what technology they use or do not use, for example when people do not have mobile phones. But that is clearly pretty dumb as it also means, for example, that all current period pieces are by default dated. Where does this argument take us?

There are times when it is relevant to say something is dated, but rarely in the way it is generally used. Acting style and ideas of realism are among things one might discuss as being dated for example, and I am all for having such discussions. But it should then mean something more than "because I did not like it".

--------------------

Unrelated but fun: the expression "the hour of the wolf" or "vargtimmen" has become a saying because of the film. The phrase and concept was invented by Bergman and did not exist beforehand. Much like The Sarah Siddons Award was invented by Joseph L. Mankiewicz when he wrote the script for his film All About Eve (1950) and then two years later it became a real prize handed out for acting in the theatre, like it had been in the film. (This year it went to Betty Buckley.)

My first reaction was, obviously, that the man was a fool and hey, there were many good films made in 1968 (Bullitt, Once Upon a Time in the West, Truffaut's Stolen Kisses, Bergman's Shame)! An angry tweet was forming. But on second thought it occurred to me that he had not said that all films were bad and that he might like those very films. By mentioning some good films from 1968 I would not disprove him and my tweet was discarded before posting. And he was right in the sense that most films from 1968 are probably not any good (imdb has 21,566 titles just from that year). But that is not something unique for films but true for works of art in general. We remember a few masterpieces and classics but the overwhelming majority of what has been created is not very good, and never was in the first place. The foolishness of him was for thinking that music was different from film. Sturgeon's law ("ninety per cent of everything is crap") probably applies there too. But such an observation is not particularly interesting.

You may think I am over-thinking that irrelevant column, written with no thought, but there is something interesting here, something this column was a good example of. The real flaw with the piece is very common, something I frequently criticise my students for, and which can even be seen as a common flaw in humans' conception of history. What does it actually mean to say that something is dated?

When that columnist said that most films have aged without dignity he made several assumptions from the fact that he did not like these films. If something has aged badly it must have been the case that it was once considered good but not so anymore. It would be weird to say that Ed Wood's films, like Plan 9 From Other Space (1959), have aged badly because they were never considered anything else than bad.

But I think we can assume that 2001, Åsa-Nisse and Where Eagles Dare are overall regarded much the same way now as in 1968. Hour of the Wolf is so strange and particular that it becomes meaningless to say it has aged in any direction. It was as weird in 1968 as it is now. You could argue instead that these films have not aged at all and the same kind of people who liked them then probably likes them now. I was a huge fan of Where Eagles Dare as a teenager, and I have it on blu-ray, but I find it a bit boring now. Not because the film has aged but because I have.

Planet of the Apes is somewhat different and it probably does not have the same kind of audience now as then. But what might conceivably be said to have aged are costumes and makeup, although I would not say they have aged without dignity. Quite the contrary.

And regardless of what one might think of those films they remain watched and liked and they continue to be a part of our culture. For that reason too it is also peculiar to argue that they have dated badly.

Some years ago a distinguished Swedish film critic said that after having re-watched The 400 Blows (François Truffaut 1959) he realised it was very dated. He did not like it as much as he once did. The presumption here is that during that time the film had changed, or aged, and he had not. I think you might more plausibly argue that it was the other way around.

The connection to my students is that they frequently say that a film is dated when they do not like it and say it was ahead of its time when they do like it. In view of the fact that they have not seen more than a small handful of older films they are not really in a position to argue whether something was ahead of its time or not. They have no frame of reference and only their prejudices to go on.

What is underlining all thinking about something being dated is an idea of progress. If an older film presents an idea of gender or sexual relations that someone today thinks is conservative or old-fashioned, she might say the film is dated; that when the film came out this was how everybody viewed gender and sexuality whereas now we have progressed and are more enlightened or some such.

But whatever view of gender or sexuality you might find in an older film can also be found in films today, and in society at large. If something is prominent today, and can be found in contemporary art, what does it mean to say it is dated? To what an extent must a view on for example social issues be less common today than it once was for that view to be considered dated? There are quite a few things in contemporary society I disapprove of but in many cases I am often in a very small minority when disapproving. It would not make any sense for me to say that a film from, say, 1952 is dated just because it is positive to one of those things I disapprove of if people today in general are just as positive about it as people were in 1952, whether I approve or not.

The beliefs that once a given film might have been considered a masterpiece but now we see that it is dated due to themes and subject matter; that something was of its time or ahead of its time; that nowadays we are wiser and more progressive and enlightened, are usually based on a smug ignorance, which can at times be quite intolerable.

It is a similar case with style. It is for example common to say that older films are slow, and that this makes them dated. As if His Girl Friday (Howard Hawks 1940) is slower than The Turin Horse (Bela Tarr 2011). Most of the current superhero films and Michael Bay's Transformers are pretty slow in the sense that they are very long, take their time, are to a large extent pointless exposition and in the end there are seemingly endless fight scenes of little value. Almost any given film from Fritz Lang' sound period, or from Darryl F. Zanuck or 1930s Warner Bros. or early Kurosawa or Bergman and so on is like a Lamborghini in comparison. Some would perhaps counter that I find The Avengers films slow because I find them uninteresting and yes, that is true. This is the point. Whether something is slow or not is a matter of personal preferences and somewhat irrelevant as a statement on cinema in general. Unless your argument is that today people find films interesting (and therefore not slow) whereas in them olden days people thought films were uninteresting and therefore slow.

There are also those who say that a film is dated because of what people wear or what technology they use or do not use, for example when people do not have mobile phones. But that is clearly pretty dumb as it also means, for example, that all current period pieces are by default dated. Where does this argument take us?

There are times when it is relevant to say something is dated, but rarely in the way it is generally used. Acting style and ideas of realism are among things one might discuss as being dated for example, and I am all for having such discussions. But it should then mean something more than "because I did not like it".

--------------------

Unrelated but fun: the expression "the hour of the wolf" or "vargtimmen" has become a saying because of the film. The phrase and concept was invented by Bergman and did not exist beforehand. Much like The Sarah Siddons Award was invented by Joseph L. Mankiewicz when he wrote the script for his film All About Eve (1950) and then two years later it became a real prize handed out for acting in the theatre, like it had been in the film. (This year it went to Betty Buckley.)

Friday 2 November 2018

Creative freedoms and final cuts

What is frequently mentioned whenever Citizen Kane (Orson Welles 1941) is brought up is Welles's contract with RKO, which allegedly gave him previously unheard-of creative freedom.

While there is no denying that Welles's contract was unusual, especially in the way it said that Welles was to have four responsibilities (actor, writer, producer and director) and a right to final cut. But disregarding the comparatively unimportant part of him also acting, this was not unique or unprecedented. Consider for example F.W. Murnau's contract with Fox for making Sunrise (1927), which gave him almost unlimited freedom (for his next two films for Fox that freedom was severely curtailed), or Ernst Lubitsch's contract with Warner Bros. in the early 1920s. ("Lubitsch shall have the sole, complete and absolute charge of the production of each such photoplay /.../ there shall be no interference of any kind whatsoever from any source, with Lubitsch, with respect to any matter or thing connected with the production, cutting and final completion of such photoplays.") That shows the high esteem in which the two Germans were held but it was not just already established directors from abroad who could get good deals in Hollywood. Consider Preston Sturges at Paramount for example, or Frank Capra at Columbia, and many other directors including some that are more or less forgotten today. Mitchell Leisen said once that since he was a "top director at Paramount" he just "snapped" his fingers and got whatever he wanted. (I wonder how accurate that was though.)

But the contract itself is not all that matters. For two case-studies let's look at two films from 1938, the year before Welles signed with RKO, at the height of the power of the studio system and at two different studies: Bringing Up Baby, made by Howard Hawks for RKO, and Jezebel, made by William Wyler for Warner Bros.

Hawks had signed a deal with RKO to make up to three films. After much time was spent on coming up with ideas and concepts Hawks settled on a short story by Hagar Wilde he had read, and called in Dudley Nichols to help make it into a feature-length script, gathered a cast and began filming. In Wyler's case, Warner Bros. already had Jezebel in mind for a film, and Wyler had many years earlier spoken about wanting to make it, so he was hired for this one film.

Once the contracts were signed Hawks and Wyler were in charge. They made all decisions, got the writers they wanted, went way over budget and over schedule, yet the studios could do nothing. The two films were made on Hawks and Wyler's terms and on their own schedules. They were responsible for the shape and form of the scripts too, and called for help with it from those they felt were right for it, in Hawks's case Nichols and in Wyler's case John Huston. (Wyler did on several occasions sign Huston up for writing or polishing scripts.) All the studios could do was hope for the best and write exasperated memos, such as one at RKO which complained that "All the directors in Hollywood are developing producer-director complexes and Hawks is going to be particularly difficult."

You could argue that Warner Bros. had been expecting to get a Warner Bros. film but instead they got a William Wyler film. But they had reason to be pleased with the finished result though, as Jezebel was a huge hit whereas Bringing Up Baby was not. RKO did not have any particular film in mind when the contract was signed but were still disappointed that they got a Howard Hawks production. Despite Hawks's deal for potentially three films only this one was made and then RKO had had enough of him.

The following year, 1939, Hawks made a film for Columbia and Wyler returned to his old partnership with Sam Goldwyn. Now though Hawks was more fortunate than Wyler, as he made Only Angels Have Wings without interference, a film that is not only one of his best but also what might be called the purest expression of all his themes and then current style. Wyler on the other hand made Wuthering Heights, where he and Goldwyn had different ideas of how it should end. Wyler's version was final and tragic, an image of Heathcliff frozen to death in the snow (the film is not a particularly faithful adaptation). That was not something Goldwyn could stomach and as Wyler refused to do a new ending Goldwyn had H.C. Potter direct a brief coda to lighten the mood, and removed Wyler's last scene.

The point is not that Hawks, Welles, Wyler, Murnau, Lubitsch were unique but that quite a few filmmakers in Hollywood could make films with great creative freedom, and not necessarily with less of it than their peers among prestigious European and Japanese filmmakers. Another point is that one must differentiate between staff directors and freelancers. A third, central, point is that the actual, lived reality in which they and all other filmmakers work is complex, constantly changing from time to time, from film to film, and often unsuitable for general theories and generalisations. It is this complexity which makes studying film history so interesting and exciting.

-------------------

Charles Vidor directed a couple of re-takes with Rita Hayworth for Only Angels Have Wings. I am not sure why, but in any event it does not effect the film.

Some sources and references:

Thomas Schatz's book The Genius of the System (1989)

Scott Eyman's book Ernst Lubitsch: Laughter in Paradise (1993)

Jan Herman's book A Talent for Trouble: The Life of Hollywood's Most Acclaimed Director, William Wyler (1995)

Todd McCarthy's book Howard Hawks - The Grey Fox of Hollywood (1997)

Vanda Krefft's book The Man Who Made the Movies: The Meteoric Rise and Tragic Fall of William Fox (2017)

Richard B. Jewell's article "How Howard Hawks Brought Baby Up: An Apologia for the Studio System" (1984)

Mitchell Leisen was interviewed by Leonard Maltin in 1970 but now I do not recall for which publication.

Speaking of lesser known filmmakers, I am curious about the contracts of someone like Mervyn LeRoy, perhaps the most successful and powerful person among the staff directors at Warner Bros. in the 1930s. Further research is definitely warranted, not just because he made such important and fine films as Little Caesar (1930), I Was a Fugitive from a Chain Gang (1932) or They Won't Forget (1937) but also because he and producers Hal B. Wallis and Darryl F. Zanuck can be said to have been particularly important in the creation of Warner Bros. particular style of filmmaking. And how did he compare to someone like Roy Del Ruth, even lesser known today yet Warner's highest paid director at the time? But having read whatever books and articles about LeRoy I could find (which was not much) I was not particularly more enlightened, other than that James Cagney was not at all a fan of him as a director or as a person.

While there is no denying that Welles's contract was unusual, especially in the way it said that Welles was to have four responsibilities (actor, writer, producer and director) and a right to final cut. But disregarding the comparatively unimportant part of him also acting, this was not unique or unprecedented. Consider for example F.W. Murnau's contract with Fox for making Sunrise (1927), which gave him almost unlimited freedom (for his next two films for Fox that freedom was severely curtailed), or Ernst Lubitsch's contract with Warner Bros. in the early 1920s. ("Lubitsch shall have the sole, complete and absolute charge of the production of each such photoplay /.../ there shall be no interference of any kind whatsoever from any source, with Lubitsch, with respect to any matter or thing connected with the production, cutting and final completion of such photoplays.") That shows the high esteem in which the two Germans were held but it was not just already established directors from abroad who could get good deals in Hollywood. Consider Preston Sturges at Paramount for example, or Frank Capra at Columbia, and many other directors including some that are more or less forgotten today. Mitchell Leisen said once that since he was a "top director at Paramount" he just "snapped" his fingers and got whatever he wanted. (I wonder how accurate that was though.)

But the contract itself is not all that matters. For two case-studies let's look at two films from 1938, the year before Welles signed with RKO, at the height of the power of the studio system and at two different studies: Bringing Up Baby, made by Howard Hawks for RKO, and Jezebel, made by William Wyler for Warner Bros.

Hawks had signed a deal with RKO to make up to three films. After much time was spent on coming up with ideas and concepts Hawks settled on a short story by Hagar Wilde he had read, and called in Dudley Nichols to help make it into a feature-length script, gathered a cast and began filming. In Wyler's case, Warner Bros. already had Jezebel in mind for a film, and Wyler had many years earlier spoken about wanting to make it, so he was hired for this one film.

Once the contracts were signed Hawks and Wyler were in charge. They made all decisions, got the writers they wanted, went way over budget and over schedule, yet the studios could do nothing. The two films were made on Hawks and Wyler's terms and on their own schedules. They were responsible for the shape and form of the scripts too, and called for help with it from those they felt were right for it, in Hawks's case Nichols and in Wyler's case John Huston. (Wyler did on several occasions sign Huston up for writing or polishing scripts.) All the studios could do was hope for the best and write exasperated memos, such as one at RKO which complained that "All the directors in Hollywood are developing producer-director complexes and Hawks is going to be particularly difficult."

You could argue that Warner Bros. had been expecting to get a Warner Bros. film but instead they got a William Wyler film. But they had reason to be pleased with the finished result though, as Jezebel was a huge hit whereas Bringing Up Baby was not. RKO did not have any particular film in mind when the contract was signed but were still disappointed that they got a Howard Hawks production. Despite Hawks's deal for potentially three films only this one was made and then RKO had had enough of him.

The following year, 1939, Hawks made a film for Columbia and Wyler returned to his old partnership with Sam Goldwyn. Now though Hawks was more fortunate than Wyler, as he made Only Angels Have Wings without interference, a film that is not only one of his best but also what might be called the purest expression of all his themes and then current style. Wyler on the other hand made Wuthering Heights, where he and Goldwyn had different ideas of how it should end. Wyler's version was final and tragic, an image of Heathcliff frozen to death in the snow (the film is not a particularly faithful adaptation). That was not something Goldwyn could stomach and as Wyler refused to do a new ending Goldwyn had H.C. Potter direct a brief coda to lighten the mood, and removed Wyler's last scene.

***

The point is not that Hawks, Welles, Wyler, Murnau, Lubitsch were unique but that quite a few filmmakers in Hollywood could make films with great creative freedom, and not necessarily with less of it than their peers among prestigious European and Japanese filmmakers. Another point is that one must differentiate between staff directors and freelancers. A third, central, point is that the actual, lived reality in which they and all other filmmakers work is complex, constantly changing from time to time, from film to film, and often unsuitable for general theories and generalisations. It is this complexity which makes studying film history so interesting and exciting.

-------------------

Charles Vidor directed a couple of re-takes with Rita Hayworth for Only Angels Have Wings. I am not sure why, but in any event it does not effect the film.

Some sources and references:

Thomas Schatz's book The Genius of the System (1989)

Scott Eyman's book Ernst Lubitsch: Laughter in Paradise (1993)

Jan Herman's book A Talent for Trouble: The Life of Hollywood's Most Acclaimed Director, William Wyler (1995)

Todd McCarthy's book Howard Hawks - The Grey Fox of Hollywood (1997)

Vanda Krefft's book The Man Who Made the Movies: The Meteoric Rise and Tragic Fall of William Fox (2017)

Richard B. Jewell's article "How Howard Hawks Brought Baby Up: An Apologia for the Studio System" (1984)

Mitchell Leisen was interviewed by Leonard Maltin in 1970 but now I do not recall for which publication.

Speaking of lesser known filmmakers, I am curious about the contracts of someone like Mervyn LeRoy, perhaps the most successful and powerful person among the staff directors at Warner Bros. in the 1930s. Further research is definitely warranted, not just because he made such important and fine films as Little Caesar (1930), I Was a Fugitive from a Chain Gang (1932) or They Won't Forget (1937) but also because he and producers Hal B. Wallis and Darryl F. Zanuck can be said to have been particularly important in the creation of Warner Bros. particular style of filmmaking. And how did he compare to someone like Roy Del Ruth, even lesser known today yet Warner's highest paid director at the time? But having read whatever books and articles about LeRoy I could find (which was not much) I was not particularly more enlightened, other than that James Cagney was not at all a fan of him as a director or as a person.

Friday 19 October 2018

Orson Welles - Part 2

But shall we wear these glories for a day?

Or shall they last, and we rejoice in them?

(King Richard, Act IV)

It was supposed to be over 20 episodes but 1955 would be Welles's last year in Europe for a while, and he never came true on his commitment to ITV. He had been in Europe since 1947 and had done all sorts of things including two films: Othello (first released in 1951) and Mr. Arkadin (1955). Also in 1955 he did a sort of meta-play of Herman Melville's novel Moby-Dick, called Moby Dick - Rehearsed, which opened at a theatre in London. Simultaneously he tried to make a film of the play but it did not go very far. 1955 was also the year in which Welles tentatively began filming Don Quixote, a project he was still working on 20 years later and never finished.

He kept himself busy in other words, with a combination of TV, theatre and film, mostly troubled productions and unfinished projects. In that respect 1955 was a pretty typical year for Welles. The name of his TV-series, Around the World with Orson Welles, is also typical. He was a fan of Jules Verne and worked at great length about doing a theatre adaptation of Verne's novel Around the World in Eighty Days. That was in 1946, and was to be produced by another Verne enthusiast, Mike Todd. Todd eventually gave up and Welles went ahead by himself, with less resources. He borrowed money from Harry Cohn at Columbia Pictures, with himself as collateral if you will since he promised to make The Lady from Shanghai (1947) in return, and Welles managed to finish the adaptation. In all there were 75 performances of Around the World (as it was called on stage), made as a musical with music by Cole Porter. The result made Bertolt Brecht exhaust to Welles: "This is the greatest thing I have seen in American theater. This is wonderful. This is what theater should be." Welles himself also thought it was among his best work.

Welles was also a global artist, from the fact that he made films and plays on several continents, was involved in politics on several continents, and had financiers from several continents. He started his travels and adventures young too, as a teenager, with for example travelling around Ireland with a donkey called Sheeog, selling paintings, and doing some bullfighting in Spain. (Many of his stories about himself and his younger years sounded outrageous and maybe not true, but more often than not they were true, such as those about Ireland and Spain.) With films you might say the global aspect began either when he did the voice-over, later removed and replaced by one done by Hemingway, for The Spanish Earth (Joris Ivens 1937), or maybe when he went to Brazil in late 1941 to make It's All True, one of his many aborted projects.

***

But he returned to the US in late 1955, did King Lear (as director and lead actor) on Broadway, played a small part in John Huston's fine film version of Moby Dick (1956) and wrote and directed his last American film, Touch of Evil (1958). It is as good as his best films of the 1940s and also highlights yet another serious problem with Pauline Kael's famous essay Raising Kane; not just for falsely attributing the script of Citizen Kane entirely to Herman J. Mankiewicz, but for making so many breezy generalisations. One of them is that Welles "has brought no more great original characters" after Kane. As an argument it is peculiar for two reasons. First because the main point of her essay is that Mankiewicz and not Welles created the character of Kane, and second because there is Hank Quinlan, the policeman played by Welles in Touch of Evil. It is such a fabulous character, one of the greatest in cinema. He is a deeply immoral man, not corrupt but damaged and rotten, and he knows it. He knows he is bad. He is a bundle of mixed emotions and contempt, long gone beyond redemption. In that way he resembles Kane. Yet look at the way his face lights up when he suddenly hears the pianola from the bordello run by Marlene Dietrich's character. It is almost like a Rosebud moment. The memory of one good thing he had but lost, in this case his relationship, such as it were, with her. Only in this case even the memory of the thing he lost is unwholesome.

In the previous Welles article I said that it is not the case that Welles directed parts of The Third Man (Carol Reed 1949). I have however always felt that Touch of Evil had something of Reed in it, not just the canted angles. Reed's films generally have an acute sense of melancholia, many are about politics across borders and they use the spaces (often cities) in which they take place to great creative effect. No film by Welles before had done that to the extent that Touch of Evil does. While not as melancholic as Reed's films (it has more anger) and filled with the peculiar restless energy that is a hallmark of Welles's work, Touch of Evil can be seen as a relative of Reed's marvellous series of city-films, from Odd Man Out (1947, Belfast) to The Third Man (Vienna), to The Man Between (1953, Berlin) to Our Man in Havana (1959). The ending of Touch of Evil in particular feels Reedian.

As is so often the case with Welles there is no proper final version, or director's cut, of Touch of Evil. At least three different versions have been released at various times although they are not that dissimilar (more a question of changes in decoupage and sound than anything about the story itself) and each has its defenders. But the 1998 version, 110 minutes long and done under the supervision of Walter Murch after instructions from Welles's famous memo from 1957, is considered closest to Welles's original intentions.

Three different versions though are nothing compared to Mr. Arkadin, of which there have been an unknown number of versions. Eight? Just the Criterion DVD has three versions: The Confidential Report (a version released in UK in 1955), "The Corinth Version" (a US release from 1962) and a new version (2006) edited by Stefan Drössler and Claude Bertemes from available previous versions. I tend to regard "The Corinth Version" as Welles's best film but since this is a contested argument I shall return to it in a later post.

***

After Touch of Evil, Welles returned to Europe and continued working on Don Quixote as well as various acting jobs. He also wrote and directed The Trial (1962), one of the films he claims was his best. It is not that but it is good, with striking locations and a unique intensity, although at times it seems to not move forward. He had creative freedom on it but it still feels unfinished, and due to financial difficulties he had to improvise and re-think a lot during the process of making it, shooting scenes on various locations around Europe, even though the film is only set in one, unnamed, place.

Something else that happened during the making of The Trial was that Welles met Olga Palinkaš, the Croatian actress and artist who became Welles's partner both in life and in art. But not under the name Olga Palinkaš, she was for whatever reason renamed Oja Kodar. Her influence on Welles was considerable, but also eventually a cause of personal pain for Welles's third, and last, wife Paolo Mori (who may for very long have been unaware of his affair) and their daughter Beatrice. Welles and Mori remained married until his death, and his relationship with Kodar lasted just as long. Kodar appears in several of his unfinished films, as well as in the exceptional F for Fake (1973), the essay film I think is one that equals Mr. Arkadin in greatness. Kodar also co-wrote and co-directed several of his later projects and often appears in documentaries about Welles. She is still involved in the restoration and promotion of his unfinished work, something that is a never-ending project.

All those unfinished and abandoned projects are part of the story of Welles, and part of the myths around him. Many see them as proof of him being a failure or a coward who did not have the courage to see his projects to the end. I think that is a mistake. We should not necessarily complain about the unfinished films but see the unfinishedness as a central part of Welles's art. He seems restless, impatient and bursting at the seams, always dashing off on some new artistic adventure and seeking finance along the way from wherever he could find it. This is part of him, part of his art and part of his genius. But he was also tenacious, keeping on working on projects for months or years, or even decades, despite one obstacle after another. That too is part of his art and genius. Just look at how impressive Othello is, despite being shot on and off for three years' time (partly in Morocco). You would not guess that it was. There is a combination of so many gifts there, improvisation and audacity in particular, and passion. Joseph McBride has argued that Welles "was a terrible businessman with a flexible sense of contractual obligations and an unfortunate tendency to deal with dubious patrons. Partly for those reasons, many of his later projects fell into legal and financial limbo." and this might be true. But his genius for filmmaking was greater than his terrible business sense.

***

Welles was many things in life and one thing in particular is that he was a raconteur, a teller of tall tales and entertainer of crowds, be they many or just an audience of one, like Kane doing shadow figures for Susan Alexander in her apartment. His films consist of several layers of storytelling, multiple stories, and people telling each other stories and fables. (The Immortal Story (1968) is a perfect example.) And he loved playing with his own voice. That voice is also more prevalent than you might realise since he dubbed many actors in for example Othello, The Trial and Chimes at Midnight (1965). He even read the credits himself in The Magnificent Ambersons (1942) and The Trial. Given this taste for storytelling and play acting, it is not surprising that his performance of the cowardly but jovial knight and performer Falstaff in Chimes at Midnight is one of his best, if not the best. The film also shows Welles's mastery and audacity, the way he manages to put several Shakespeare plays together, and film it in Spain under severe budget restraints, yet the result is superb and spellbinding, and with a performance by Welles that also captures the man himself.

***

Spain was an important country for Welles all through his life, from his early days as a potential bullfighter. He lived there for many years, and made several projects there. This is also where he is buried, appropriately enough in a well. It was his daughter Beatrice who placed his ashes there, together with her mother's, in 1987, two years after Welles's death. Oja Kodar thinks this is a disgrace and against Welles's wishes; him being entrapped instead of scattered for the wind. I do not know anything about his wishes, but how could he be buried anywhere else?

Photo from a hotel in Ronda, where the well is located.

------------------------

This was my second article on Welles. The first is here. There will be another.

The Brecht quote is from James K. Lyon's book Bertolt Brecht in America (1980) p. 179

The quote from Joseph McBride is from his book Whatever Happened to Orson Welles (2006) p. 15

Moby-Dick was often on Welles's mind. He tried to make a film version of it in 1971 but it was never finished. He also tried in 1947.

There is a good documentary done with Oja Kodar about unfinished films, Orson Welles: The One-Man Band (Vassili Silovic, Oja Kodar 1995). I recommend it.

I wrote about Carol Reed three years ago, here.

The same year as Chimes at Midnight, Welles played Cardinal Wolsey in Fred Zinnemann's version of Robert Bolt's A Man for All Seasons. A great performance in a great film, as a man eaten alive by the colour red.

Etiketter:

authorship,

Carol Reed,

film history,

Orson Welles

Friday 5 October 2018

Orson Welles - Part 1

As if a man were author of himself,

And knew no other kin.

(from Coriolanus, Act V)

(from Coriolanus, Act V)

When Kane and Susan Alexander go on a picnic towards the end of Citizen Kane (Orson Welles 1941), a band is playing "It Can't Be Love" (aka "In the Mizz", sung by Alton Redd) to entertain the guests while in a tent Kane and Alexander are having a fight. The sound we hear through the scene is that song in the background and their angry voices. After a while Kane says that whatever he did it was because he loved her but she replies that he did not really love her. He did it so that she would love him she says, that this is the only thing he ever cared about; to be loved. When she says that, clearly a soft spot, he slaps her face. She barely blinks and just looks back at him. "Don't tell me you're sorry." she says coldly and he replies "I'm not sorry." An ordinary scene. But right after he slapped her the sound of "It Can't Be Love" in the background disappears and instead we hear a woman screaming. The people outside cannot have seen or heard what was happening in the tent so it is unrelated, and it is obviously not Alexander that is screaming because we see that she does not. Is it perhaps in Kane's imagination that Alexander screams? Or is she screaming on the inside so we hear how she feels, even though she hides it from Kane? Is the sound diegetic or non-diegetic? It is one of those touches that Citizen Kane is filled with and that makes it such a rich and fabulous film.

Citizen Kane is also a film about which at least half of what is considered conventional wisdom is more or less myths. The two-hour long documentary that accompanied the DVD I happen to have begins by stating that Welles's contract with RKO gave him creative freedom of a kind nobody had ever had in Hollywood before, which is a clear exaggeration since Welles did not get unlimited control and many other filmmakers had done films before with similar autonomy (and it seems there were three contracts between Welles and RKO, not just one). It was also said that Citizen Kane was the peak of Welles's career and nothing he made after that can compare to it. The latter is of course a subjective opinion so I cannot say it is not true. I would say though that such an opinion is rarely based on an actual comparison between it and Welles's later films, and is instead taken for granted for no particular reason.

There is no denying that Citizen Kane is important; a landmark, a benchmark, and a very good film. But it is often spoken about in ways that are not helpful; not for it, for its place within Hollywood or for Welles's career in general. Many still seems not to recognise that it did not invent deep focus (it has been in use as a creative component since at least the 1910s), or that many of the alleged deep focus shots were created in post-production by the use of an optical printer. This of course does not diminish the film or the cinematography, it just slightly adjusts the focus from the cinematographer Gregg Toland to Vernon L. Walker, RKO's head of special effects, and Linwood G. Dunn from the special effects team who were responsible for the creation of many of the shots and tricks in the film. Dunn had invented the optical printer, and incidentally he is the man responsible for creating the illusion of Cary Grant, Katherine Hepburn and the leopard appearing together in Bringing Up Baby (Howard Hawks 1938). (A filmmaker who had had the same creative freedom as Welles.)

Speaking subjectively, I do not think Citizen Kane is Welles's best film. His second one, The Magnificent Ambersons (1942), is just as good, despite being only available in an 85 minutes long version of what was originally 130 minutes. (Although the 130 minutes version was not finished either, it was still a work in process and should not by default be called the real version, or a director's cut.) It is a melancholic and leisurely film about the fall of a wealthy family and the passing of time into modernity; filled with love and life, and lingering moments, and in many ways very different from Citizen Kane. That feels like the work of an ambitious young man, eager to show off, while The Magnificent Ambersons feels like the work of a wise old man with nothing to prove. Yet it is still dazzling. The ball sequence is incredible for example.

Welles's other films of the 1940s I am less keen on. The Stranger (1946), about a suspected Nazi hiding in plain sight in a small American town, has a good performance by Edward G. Robinson but that's about it. It is not a bad film, but the script by Anthony Veiller and John Huston, and Welles, feels like it would have suited Alfred Hitchcock better. The Lady from Shanghai (1948), an erotic thriller of sorts, is rather awkward. It is too wayward, awkwardly paced, I feel very little emotional engagement with anything going on, and it has a rather embarrassing performance from Welles himself as the Irish, or "Irish", Michael O'Hara. This is not all the fault of Welles as it was taken out of his hands and cut down and truncated (as was The Stranger to a lesser extent), so issues with the pacing and such things might better be blamed on Harry Cohn, the boss of the studio that produced it, Columbia. But while The Magnificent Ambersons is a great film despite being cut down, The Lady from Shanghai is, I think, not a great film, and Welles's performance is not Cohn's fault. But the film is audacious and fascinating, and the fun house mirror sequence towards the end however is spectacular and mesmerising, almost better than anything in Citizen Kane. In his fine book The Magic World of Orson Welles, James Naremore calls The Lady from Shanghai "the radicalization of style" and the film certainly has a radical style.

Welles's next film Macbeth (1948), an interesting mixture of theatricality and cinematic inventiveness, is fine but not Welles's best Shakespeare adaptation. As an example of how to make good use of a cheap production and abandoned sets it is rather impressive however.

There were two films in 1943 to which Welles contributed a lot, uncredited. On Jane Eyre, in which Welles played Rochester, he was heavily involved in the production, including set design, writing and editing and with a say in casting. The film has great photography by George Barnes and its look is the best thing about it. Pure English gothic. It seems Robert Stevenson still was principally in charge of direction, and it had been a pet project for him. It was the first film where Welles was directed by somebody else, unless you count the voice-over narration he did for Swiss Family Robinson (Edward Ludwig 1940).

Despite their originalities and personal quirks however, the films Welles made in Hollywood in the 1940s are not better than many other films made there at the same time, and many films from his contemporary peers (such as Ophuls, Ford, Hawks, Lubitsch, Preminger and Hitchcock) are considerably better. No, I think it was in the 1950s and onwards that Welles really reached a new level and from which it is more relevant to speak of him as a unique filmmaker, perhaps a filmmaker of genius.

***

One of the things that make Welles's films so special was there from the beginning: himself. Not necessarily his general acting abilities but his persona and his voice. He does a truly wonderful voice-over in The Magnificent Ambersons and he kept doing so for several of his, and others', films. It is a rich, colourful, deep voice, a mixture of wistfulness, wit and wisdom, and sometimes an amused weariness, which can be intoxicating. (Many of his early radio performances are available on Spotify.)