The previous post introduced my exploration of the period from 1930 to 1945 in Hollywood. I want to do several things, spread out over several posts. One thing is to compare what prominent

historians are saying about the period with what the figures tell us in

terms of popularity. Another is to look at trends in moviegoing habits.

Another is to compare studios in terms of how well they did at the box

office and at the Oscars, and how that evolved over time. Another is to

look at what kinds of films were most popular at any given time,

compared with what kinds of films were nominated for Oscars, and how

that evolved over time. I also want to look at the 1938 piece in The Hollywood Report that made "box office poison" a known term, and see how the actors in question were doing before and after 1938. Actors will be the focus of the next article. In this article the focus is on which films, studios, directors, and genres were the most successful.

None

of this will tell us anything about the strengths and weaknesses of the

individual films, or much about the art and craft of filmmaking. But it

can be interesting as sociology and as history.

One difficulty is to figure out the reliability of the box office statistics. You cannot rely on just one source (such as Wikipedia's top ten lists of each year) as there are many mistakes in most, or possibly all, of them, and also different ways of measuring and reporting the numbers. A film's reported rentals are sometimes only domestic (which I prefer) and sometimes international. Some lists include only the numbers for the film's first release (again my preference) and others include subsequent

re-releases. In some cases, a top ten list from a given year will only contain the films released in that year, even if a film released late in the previous year was the most popular one for the year in question. On the other hand, a list of the most successful films of 1942 might not include Casablanca, even though it was released that year, because most people saw it in the beginning of 1943. Another example is National Velvet, which opened in mid-December of 1944. If half of a film's audience is at the end of one year and the second half at the beginning of the next year, the film might be very successful yet not appear on any list.

Sometimes films are inexplicably missing from a list. I have seen a list of the most successful films of 1972 that did not include The Godfather and I have seen lists of the most successful films of 1930 that did not include All Quiet on the Western Front, despite each film being among the greatest hits of their respective years. Another summary, of the most successful films of the 1960s, did not include My Fair Lady (1964) even though it should have been.

The various studios are not equally good or reliable at reporting and/or saving their box office statistics, so, for example, figures for MGM, Warner Bros. (WB), and Twentieth Century-Fox seem more dependable than Universal, Paramount and Columbia for some reason. Another problem is that the figures for certain kinds of films, such as those with Shirley Temple, seems to be underreported. Only one of Temple's films appear in my figures, but that is not necessarily the only one that did make it into the top ten. The same is true for the films Deanna Durbin did at Universal in the second half of the 1930s. One of them appears now, One Hundred Men and a Girl (1937), but I am convinced that one or two more should be included. So far I do not have the figures to support my belief.

One reason why film historians, and especially those more interested in theory, slip up is because of these errors. Robert B. Ray tries to strengthen his tenuous arguments in A Certain Tendency of the Hollywood Cinema 1930 to 1980 by referring to box office statistics but his source is not reliable, and neither is his readings of that source. He claims for example that Josef von Sternberg's films were unpopular, and that both All Quiet on the Western Front and I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang (1932) failed at the box office. Neither of these statements are true, but since his arguments to some extent need them to be true one can see why he would make them. (But I might write more on Ray's book in a later article.)

I have used several different sources myself, including Wikipedia, Joel W. Finler's book

The Hollywood Story,

Variety,

The Hollywood Reporter, an article from 1944 in

The Argus Weekend Magazine,

some articles from Historical Journal of Film, Radio & Television, some box office reporting in Motion Picture Almanac, and some other books and sources. I have then compared the figures from each year for these different sources to try to

get as close to the truth as possible. It still remains the case that

my box office lists, especially for the earlier years of the 1930s,

cannot be taken as the last word on the subject, but they are

interesting and relevant, and they give a good idea of what was doing

well in terms of audience numbers.

Another important point to

make though is that doing well in terms of sold tickets does not mean by

default that the film was profitable. As regularly happens, a studio

will spend too much on a film and it will not recover its costs even if

it is the most successful film of the year. This happened a lot in the

late 1960s as I mentioned in an earlier article, and it happened in the

1930s as well. But this too can be confusing, and one of my sources, The Hollywood Story, will illustrate it. Finler says on page 43 that The Adventures of Robin Hood

(1938) "cost a hefty $1.9 million and thus earned only a small profit."

but on page 301 he writes "Biggest disappointment of all [for WB in 1938] was the outstanding Errol Flynn vehicle, The Adventures of Robin Hood,

which was filmed in Technicolor at a cost of almost $2 million but

failed to earn a profit." It cannot be true that it both made a profit

and failed to make a profit. According to figures from WB.'s

own records, the film took in $4 million in revenues (domestic and

international) which means it took in twice the amount it cost to make it. This does not mean all that money went back to WB as there were probably other expenses as well. But working out exactly what the profit for the film was is difficult.

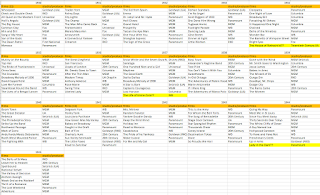

That is enough background and caveats for now. Let us instead turn to some statistics. The first table is the most successful films for each year from 1930 to 1945, with the name of the studio or, in some cases, independent producer included. As you will see, MGM was the dominant studio almost every year. One more clarification though. Only one of Disney's animated films are listed below and that is because, overall, they make a lot of their money on repeated re-releases. Pinocchio (1940) and Bambi (1942) are among the most successful films of all time, but that built up over the decades.

The ambition has been to put them in the order of reported rental

returns, with the most successful film at the top, but as I have said it

is not an exact science. For many films of a given year the reported

rentals are almost the same, and sometimes they are estimates. You will

often see this or that film described as "the second-highest grossing

film of the year" or "it was a huge success, being the fifth most

popular film of 1936" but you cannot say that with any kind of

certainty. "Among the ten most popular" is usually as close as you will

get. It is also rare for this period for one film to be considerably

more successful than the next one. Only three stand out their respective years, Gone with the Wind (1939), Sergeant York (1941) and Bells of St. Mary's (1945). Most other films follow each other closely.

Three films, The House of Rothschild (1934), The Life of Emile Zola (1937), and Lady in the Dark

(1944), are followed with ?? and highlighted in yellow, and this is

because the figures for them are unclear so I am not sure whether to

include them or exclude them.

Here are the number of film(s) for each studio or independent producer among the 165 titles that have been included:

Disney (1 film), First

National (1 film), Twentieth

Century (1 film), UA - United Artists (4 films, 3 being Chaplin's), Universal (4 films), David O. Selznick (5 films), Fox (6 films), RKO (7 films), Columbia (8 films, 5 being Capra's), Twentieth Century-Fox (12 films), Samuel Goldwyn (12 films), WB (18 films), Paramount (28 films), and MGM (58 films).

Given that MGM was the most successful company it would seem that the most successful directors were those working for MGM, but it is not quite so straightforward. This leads to a question worth pursuing. To what extent, or rather in which cases, the director could be said to be responsible for its success and to what extent a film was primarily a success due to the "genius of the system". I will not dig into this now, but as an example the successes that W.S. Van Dyke had in the first half of the 1930s might be attributed more to him personally (as the films were his ideas and made under his control) and the successes he had in the later part of the 1930s might be attributed more to MGM (as they were conceived by others in the studio and he had less control). The answer to the general question though is that it depends on who the director is, with which studio he is associated, and whether he is a contracted one or a freelancer.

Here you can see which directors made the top ten films of each year. Given the importance of Busby Berkeley, I have underlined the films on which he participated in some capacity even if it was not as director of the whole film:

There are 165 films but only 66 directors. The following have made five or more films:

Clarence

Brown (mainly MGM), Frank

Capra (Columbia), Mervyn

LeRoy (WB and MGM), Michael

Curtiz (WB), and Cecil B. DeMille (Paramount) had 5 films each. George Cukor (three studios) and Henry

King (Fox and Twentieth Century-Fox) had 6 films each. Victor Fleming (Fox and MGM) had 7 films, and Van Dyke 8 films, all for MGM.

More interesting is to look at genres. I have in the document below given each film a genre categorisation. This is not easy, and many of these might be open to discussion. Some are more general, and others are more specific. "Musical" is too general for me. I have used it for 44 of the 165 films, but I have tried to specify it a bit, to "musical comedy" or "musical drama" for example. (Some of the musicals might be better referred to as "operettas" but I did not do that this time.) In one case I refer to it as a "Minnelli musical" as some films have their own particular ambiance which can be attributed to the director. Hence, I have called Steamboat Round the Bend (1935) a "John Ford comedy" and I could perhaps have used "Capra comedy" for You Can't Take It with You (1938). But you can see for yourself here:

What this highlights is the complexity of the issue of genres. It is not the case that the genre definitions or, better, suggestions, I have given are necessarily what the studios used themselves, and the critics and the audiences might probably have used other ones. And as you can also see, there are few pure genre films. It is often a combination of different things, and sometimes it is the stars that provide the genre. There is enough material here for a book on Hollywood and its relationship with genres, so a deeper analysis will have to wait for another article. This will be all for this post.

In the next post I shall be looking at actors (which to a large extent means Clark Gable).

-----------------------------

Part I is here: https://fredrikonfilm.blogspot.com/2021/03/1930-to-1945-by-numbers-part-i.html

Part III: https://fredrikonfilm.blogspot.com/2021/04/1930-to-1945-by-numbers-part-iii-actors.html

More about W.S. Van Dyke here: https://fredrikonfilm.blogspot.com/2020/10/ws-van-dyke-and-myrna-loy.html

List of all sources and resources will appear in the last article of this project.

(Shortly after publishing I updated the genre/style tables for five films for more clarity.)